Stakeholder theory, stockholder primacy laws and challenge to same

Grant Rozeboom

Learning Objectives

At the end of this module, you will be able to

- Explain the differences and overlap between shareholder-primacy and stakeholder-primacy approaches.

Comprehension Questions

While reading this chapter, consider

- What are some of a company’s stakeholder groups in addition to its shareholders?

- When and why does stakeholder-focused management issue in different decisions from shareholder-focused management?

Social Responsibilities

An important aspect of navigating a morally responsible path through business organizations is helping them to fulfill their social responsibilities – their obligations as members of their societies. We are not just responsible as individuals for reasoning well and upholding our values. We are also responsible as members of organizations for helping ensure that how they operate and the impact they have is justifiable within their social context.

Of course, any appeal to the idea of “responsibilities” immediately raises the question: responsible to whom? And for what? These are the central questions in debates about the scope and implications of corporate social responsibility (CSR). You need to understand these debates to be well-informed future employees and leaders in organizations that are legitimately expected to be socially responsible. We will begin with an overview of one of the most foundational issues of CSR—the difference between shareholder-focused and stakeholder-focused management practices.

Fiduciary Obligations

Remember that one of the foundational normative ideas in business is that of the fiduciary obligations that managers hold toward shareholders. Managers are entrusted by shareholders with the discretion to run companies in ways that promote shareholder interests. This is a natural place to begin when thinking about the social responsibilities of business. The view that takes it most seriously (some would say too seriously) is “shareholder primacy,” or what we can call shareholder-focused management. This view is partly reflected in corporate law, especially the corporate laws in the U.S. state of Delaware.

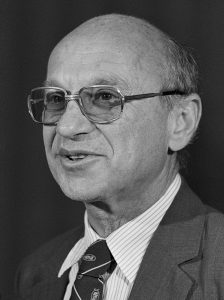

To understand this perspective, we’re going to work through a guided reading of the essay that defined, at least in popular practice, the phenomenon of shareholder-focused management. This is Milton Friedman’s “The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits” [New Tab]. Select the link to access the article.

(i) Friedman begins with the same general question we’re concerned with: How should we understand the social responsibilities of business organizations? He then moves to focus on the fiduciary responsibility that corporate managers, especially executives, have to shareholders. Take some time to take note of how Friedman understands this responsibility. What does he mean when he labels corporate managers “employees”?

(ii) Friedman then criticizes what he views as a common mistake in how people of his day talked about the social responsibility of businesses. What is this mistake, and why is it mistake? A clue: it has centrally to do with what Friedman describes as executives “spending someone else’s money” and, a bit later, as acting “simultaneously as legislator, executive, and jurist.”

(iii) Friedman makes two important qualifications to his claim that business leaders should focus primarily on generating profits for owners (or shareholders). First, he claims that a sole proprietor (or owner-operator) is free to use their business’ earnings to engage in socially beneficial activity. Why? Second, he claims that it is permissible for the managers of corporations to use their resources to engage in socially beneficial activity when it is in the business’ “long-run interest.” What does this mean, and how does it align with his central view about what corporate managers are responsible for?

It is worth noting that Friedman’s view, while popular, was widely misunderstood. It was taken as license for institutional investors and executives to drive up their wealth through short-term cost-cutting strategies, the exploitation of information asymmetries in stock markets, and taking advantage of bargaining asymmetries with workers. Perhaps Friedman could and should have done more to forestall these distortions of his view, but we should not perpetuate the mischaracterization of it.

Additional Stakeholders

Friedman’s shareholder-primacy view starts with the thought that managers are responsible to shareholders in virtue of the stake that shareholders have in corporations. R. Edward Freeman shifted the direction of thought and practice of corporate social responsibility by asking: What other groups and constituencies also have a stake in corporations, in addition to shareholders? Think about it this way: It is natural to suppose that shareholders matter for managerial decision-making because they depend on corporations for generating a return on their investment, and corporations depend on them for their continued investment in order to build facilities, expand their workforces, fund research and development, etc. There is persistent, mutual dependence between shareholders and corporations. For what other groups of individuals is this true? It certainly seems true of employees: They depend on corporations for their livelihood, professional growth, and economic stability. And corporations depend on their employees for getting the work done—the making and selling of the corporation’s products and services.

Now consider customers. How do they depend on corporations, and how do corporations depend on them, in an ongoing way? Local communities, within which corporations operate? Suppliers, for whom corporations serve as customers?

These are all stakeholder groups. Freeman argues that they should be treated as on a par with shareholders for how they matter in managerial decision-making, because they share with shareholders the morally and strategically important property of being bound to corporations through ties of mutual dependence. They all have a stake in the corporation and its success.

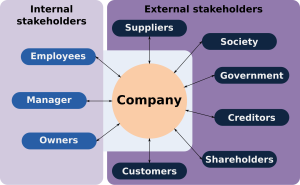

Figure 5.5. Any one company has a variety of internal and external stakeholders. [Image Description]

If Friedman advocated for shareholder primacy in managerial decision-making, Freeman can be thought of as advocating for stakeholder equality. The impact of managerial decisions on any stakeholder group should not be ignored, and no one stakeholder group should always receive priority over the others.

You might immediately notice that, if we take Freeman’s stakeholder equality idea seriously, we have to contend with the reality of tradeoffs between stakeholder groups. Sometimes a manager must choose between doing what is good for one stakeholder group and what is good for another. For instance, as you’ll explore below, sometimes what is good for employees may put a dent in the financial returns that shareholders receive. Is there any principled guidance for managers who want to implement the stakeholder equality approach and face these difficult tradeoff scenarios?

There are two general strategies to consider here: The first considers stakeholder power. It evaluates which stakeholder group is most capable of inflicting harm on a firm, should its interests be sacrificed for another group of stakeholders, and it tells managers to prioritize the more powerful stakeholder groups. A straightforward, and potentially worrisome, implication of this strategy is that stakeholders that are socially marginalized and relatively powerless are to be deprioritized, precisely because they lack power. A second strategy that avoids this problem considers stakeholder legitimacy. That is, it evaluates which stakeholders have the most pressing moral claims on the corporation in a given scenario, and it tells managers to prioritize those stakeholder groups. Sometimes stakeholders might have the most pressing moral claims even though—or perhaps precisely because—they have little social power.

Applying Two Approaches

Now let’s practice applying the two approaches to corporate social responsibility we’ve just explored, to better understand what they entail and how they differ. First, read through this short article [New Tab] about some decisions that American Airlines made that upset its shareholders a few years ago.

First imagine working through the key decision(s) that the American Airlines (AA) CEO made using the shareholder primacy approach. Would you have made a similar, or different, decision? Notice that the CEO tried to justify his decision in shareholder-friendly terms, by appealing to its long-term financial effects. One thing we need to keep in mind is that shareholder financial interests need not, and probably should not, be understood as being satisfiable in a short-term (e.g., quarterly) manner.

Next imagine making the key decision(s) using the stakeholder equality approach. Would you have made a similar, or different, decision? Why or why not?

You may have noticed that, sometimes, the shareholder primacy and stakeholder equality approaches point in the same direction. What is good for shareholders ends up being good for other stakeholder groups, too. It’s nice when this occurs, but when it doesn’t, the approaches diverge and, on the stakeholder equality view, a principled decision needs to be made about how to manage the tradeoffs between different stakeholder groups.

References

Freeman, R.E. (1984). Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Cambridge University Press.

Image Descriptions

Figure 5.5. This diagram visualizes a company’s internal and external stakeholders using a hub-and-spoke layout. At the center is a circle labeled Company, surrounded by labeled rectangular boxes connected by lines. On the left side, under the heading Internal stakeholders, three blue boxes labeled Employees, Manager, and Owners are connected to the company. On the right side, under the heading External stakeholders, six boxes labeled Suppliers, Customers, Society, Government, Creditors, and Shareholders link to the company. The layout emphasizes the range of parties with interests in a company’s operations, distinguishing between those inside the organization and those outside it. [Return to Figure 5.5]

Media Attributions

- Milton_Friedman_1976

- Stakeholder_(en).svg