Corporate Social Responsibility

Caroline Burns Ph.D

Learning Objectives

At the end of this module, you will be able to

- Define Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and explain why it is difficult to define clearly.

- Describe how ideas about CSR have changed over time, including key turning points and debates.

- Identify five types of CSR practice and explain how they reflect different views about what responsibility means.

At first glance, Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) seems like a simple idea: that businesses should be accountable not only to shareholders, but also to society at large. Yet when we try to define and describe it, it becomes obvious that the social responsibility of business is not only hard to define and describe, but there isn’t even an agreeable best approach when considering all that could be done and how we define society.

Some understand CSR as a firm’s ethical position, while others see it as a business strategy. Some emphasize voluntary commitments while others demand legal regulation. In some cases, CSR is framed as adherence to law, while others argue it is a distraction from structural reform owed to society and the environment.

This chapter explores CSR not as a checklist, but as a series of tensions. We begin by examining the basics, its history, etc., and then move to the tension between stakeholder and stockholder perspectives on the social responsibility of the firm, and theories of responsibility inside the firm. We then separate out the firm’s responsibility to the environment, and finally, we explore how public pressure and consumer activism challenge businesses to account for their impact.

Defining CSR

Basically, CSR refers to the expectations placed on businesses to act with consideration for their wider social and environmental impact. These responsibilities may involve legal compliance, ethical internal decision-making, public transparency, efforts to support social equity, and environmental sustainability. But definitions differ depending on context. Is CSR an extension of profit-seeking, or a moral constraint on it? Is it a discretionary initiative or a basic obligation? The term carries normative weight and invites reflection on what it means for a business to act justly in a world where economic actions have political, social, and ecological consequences.

A Brief History of CSR

Corporate Social Responsibility has a long history of big promises and disappointing results. Early corporate philanthropy was selective and self-serving. Factory owners built hospitals while at the same time maintaining exploitative working conditions. This pattern of charitable gestures without structural change established a troubling precedent that persists today.

Howard Bowen’s 1953 book, Social Responsibilities of the Businessman, argued that large firms had moral obligations beyond profit-making. Bowen positioned corporate responsibility as a fundamental business duty rather than an optional charity. Though his influence was limited at the time, his perspective is foundational in CSR scholarship. However, his ideas found little practical application because they lacked supporting institutional frameworks and clear business incentives.

Milton Friedman’s 1970 New York Times article, “The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits,”[1] directly challenged the entire CSR project. His perspective, which we will explore in more detail later in the chapter, was that the social responsibility of business was simply to increase its profits and that in itself was socially responsible. CSR, Friedman argued, distorted market capitalism by forcing executives to make social decisions they were not qualified to make. His critique gained widespread acceptance during the deregulation wave of the 1980s, effectively sidelining CSR in many business circles and creating a lasting division between those who view social responsibility as integral to business and those who regard it as a distraction.

Figure 5.1. In their seminal pieces on CSR, Howard Bowen (left) and Milton Friedman (right) had differing opinions of the responsibilities of profit. [Image Description]

Archie Carroll’s 1991 journal article “Pyramid of CSR,” published in the academic journal Business Horizons, aimed to create a clear definitional framework by distinguishing economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropic responsibilities. Carroll built his framework around the concept of a pyramid, and placed economic responsibility at the base as the foundation for other responsibilities. Carroll’s work became the most widely taught CSR framework in business schools, though it has also been criticized for masking the tensions between profit motives and social obligations.

Figure 5.2. Carroll’s Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibility. Archie B. Carroll, which is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 license. [Image Description]

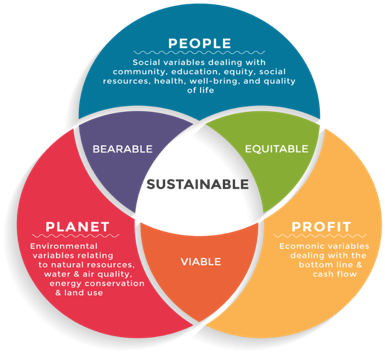

The 1990s saw attempts to broaden CSR’s practical application. John Elkington’s concept of the “Triple Bottom Line,” suggested companies could measure success through people, planet, and profit simultaneously. High-profile scandals such as Shell’s operations in Nigeria and Nike’s supply chain controversies sparked public backlash and increased pressure for public accountability, thus the focus on reporting out on people, profit, and planet.

Figure 5.3. An illustration showing the intersections of people, planet, and profit of the Triple Bottom Line. Image created by Marten van den Berg, ChainPoint, 2018. [Image Description]

Michael Porter and Mark Kramer’s concept of Creating Shared Value, first introduced in a January 2011 Harvard Business Review article, attempted to reframe CSR by placing social progress at the heart of business strategy. They argued the capitalist system was “under siege” and proposed that firms could generate economic value in ways that also produced social value. Unlike earlier CSR models, which often treated social impact as a cost or afterthought, their approach suggested that business success and societal progress could be mutually reinforcing.

Typologies of CSR Practice

Despite it being a long-standing business concept and strategy, CSR is not practiced uniformly. Firms vary widely in their motivations, level of commitment, and institutional integration.

Defensive CSR: “Do the minimum, avoid the damage”

This strategy is reactive. Firms adopt ethical policies or social initiatives primarily to pre-empt criticism, manage risk, or avoid regulatory intervention. Examples include publishing a diversity statement after a public controversy or announcing carbon neutrality goals with no clear implementation plan. Defensive CSR is often superficial and is less about reform, more about reputational insurance.

Charitable CSR: “Give back, but don’t change”

Philanthropy remains a popular and visible form of CSR. Donations to schools, hospitals, or cultural programs can benefit communities, but are often disconnected from the core business model. This approach reinforces the idea that firms can generate profit in one domain and compensate for their negative social and environmental consequences in another.

Strategic CSR: “Do well by doing good”

In this model, CSR initiatives are aligned with profit motives. A company might adopt sustainable packaging to reduce costs or promote fair labor practices to improve brand loyalty. When values and strategy align, this can produce shared value; that said, the commitment often remains conditional in that social and environmental goals are pursued as long as they are commercially viable.

Integrative CSR: “Responsibility is how we do business”

Here, CSR is embedded into governance, operations, and long-term planning. The firm views ethical responsibility not as an external add-on but as an internal standard. This may involve non-financial metrics, sustainability initiatives, diversity goals, and stakeholder consultation as a regular feature of decision-making. It also acknowledges that trade-offs may be necessary and that ethical choices are not always cost-neutral.

Transformative CSR: “Change the system, not just your company”

Rare but increasingly visible, this model reflects a deeper social and environmental ambition. Firms engaged in transformative CSR may lobby for stronger labor laws, shift to regenerative business models, or challenge the assumptions of perpetual growth. These firms treat themselves as social and political actors, not merely economic ones.

As the above discussion makes clear, there is no single way that businesses approach social responsibility. Strategies vary not only in ambition but in underlying assumptions about what responsibility entails. Before examining how these commitments are implemented, it is necessary to ask a more basic question: responsibility to whom? Some in business argue that firms owe duties to a broad network of stakeholders. Others insist that their only obligation is to shareholders. To evaluate these competing views, we turn to two influential but opposing perspectives: those of Edward Freeman and Milton Friedman.

Knowledge check

References

Bowen, H. R. (2013). Social responsibilities of the businessman. University of Iowa Press.

Carroll, A. B. (1991). The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Business Horizons, 34(4), 39-48.

Elkington, J. (1998). Cannibals with forks: The triple bottom line of sustainability. Gabriola Island: New Society Publishers.

Friedman, M. (1970, September 13). The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. New York Times, Section SM, Page 17.

Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2011). Creating shared value. Harvard Business Review, 89, 62-77.

Image Descriptions

Figure 5.1. This image presents a side-by-side comparison of two influential figures in the field of corporate social responsibility (CSR). On the left is a black-and-white portrait of Howard R. Bowen, wearing dark-rimmed glasses, a suit, and tie. Overlaying the bottom of his portrait is the blue cover of his book titled Social Responsibilities of the Businessman. On the right is a black-and-white portrait of Milton Friedman, also wearing glasses, a suit, and tie. Overlaying his image is a clipping from his famous 1970 New York Times essay, with the headline: A Friedman doctrine—The Social Responsibility Of Business Is to Increase Its Profits. The visual juxtaposition underscores the contrasting views of Bowen, who advocated for ethical and social responsibilities in business, and Friedman, who emphasized profit maximization as the primary duty of corporations. [Return to Figure 5.1]

Figure 5.2. This image displays Carroll’s Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibility, structured as a four-layer triangle with the broadest layer at the base and the narrowest at the top. Each layer represents a different level of responsibility businesses have toward society. At the bottom is Economic Responsibilities, labeled “Be profitable” and noted as “Required by society.” Just above it is Legal Responsibilities, labeled “Obey laws & regulations,” also marked as “Required by society.” The third tier is Ethical Responsibilities, which include “Do what is just and fair” and “Avoid harm,” labeled as “Expected by society.” At the top of the pyramid is Philanthropic Responsibilities, labeled “Be a good corporate citizen” and described as “Desired by society.” Dashed lines divide each section horizontally. The diagram emphasizes that while profitability and legality are foundational and required, ethics and philanthropy reflect society’s expectations and desires for corporate citizenship. [Return to Figure 5.2]

Figure 5.3. This image illustrates the Triple Bottom Line framework using a Venn diagram of three overlapping circles labeled People, Planet, and Profit. Each circle represents a key domain of sustainability. The People section is blue and includes “Social variables dealing with community, education, equity, social resources, health, well-being, and quality of life.” The Planet section is red and describes “Environmental variables relating to natural resources, water & air quality, energy conservation, and land use.” The Profit section is orange and refers to “Economic variables dealing with the bottom line & cash flow.” Where People and Planet overlap, the area is labeled Bearable; where People and Profit intersect, it’s labeled Equitable; and where Planet and Profit meet, the intersection is labeled Viable. At the center, where all three circles overlap, the area is labeled Sustainable, indicating the ideal integration of social, environmental, and economic concerns. [Return to Figure 5.3]

Media Attributions

- bowen_friendman

- Carroll’s Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibility

- Picture4

- This New York Times article and other pieces mentioned in this chapter are behind paywalls. See your library for cost-free access. ↵

Changes aimed at correcting underlying systemic problems rather than addressing symptoms or offering surface solutions.

The formal and informal structures (e.g., laws, norms, enforcement bodies) that shape how businesses behave and define responsibility.

A framework that assesses corporate performance across social (people), environmental (planet), and financial (profit) dimensions.

The principle that firms should be answerable to the public, not only to shareholders or voluntary codes.

The structures and processes by which firms are directed and controlled. Governance defines who has authority, how decisions are made, and how accountability is upheld.

Situations where pursuing one goal (e.g., profit) may require compromising another (e.g., fairness or sustainability).

An entity, such as a corporation, that influences public policy, law, or social norms and not just market outcomes.