Aristotelian ethics

Grant Rozeboom

Learning Objectives

At the end of this module, you will be able to

- Demonstrate in writing or conversation how the key Aristotelian ethics principles apply to concrete decision-making cases.

1.

A distinctive feature of the care ethics view is that the principle it supplies requires us to imagine being (and ideally actually be) care-minded. We cannot engage in ethical reasoning using the care-ethics principle without deeply understanding what it is to be care-minded. This raises an important question about ethical reasoning: What if what’s important about ethical reasoning is not our choice of principles but the attitudes and traits from which our reasoning proceeds? That is, what if what matters most is having the right kind of character, and reasoning well simply flows from this?

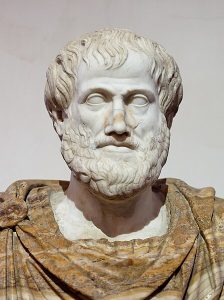

This “what if” is taken most seriously by the branch of ethical theory called “virtue ethics.” Its most common form is Aristotelianism, taken from the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle. Virtue ethics wants us to focus on cultivating the right forms of character and to treat ethical reasoning as downstream of manifesting the right forms of character. The question for us, then, is what it looks like to sustain morally good character traits in challenging organizational situations, such as the one faced by Kathleen Fitzgerald at Wells Fargo.

2.

Character traits, in general, are stable dispositions to feel, think, and act in certain ways. When we say things such as, “He’s quite a nice guy,” or “They’re a bit mean-spirited,” we have in mind how someone is disposed to feel, think, and act in a wide range of situations. We are expressing a characterization of who they are in general—the traits that define the kind of person they are. Of course, everyone sometimes acts “out of character,” but the idea of a character trait is meant to capture the general ways that people are prone to respond. (Social psychologists have now arrived at a more nuanced understanding of what character traits are and how they interact with persons’ environments—we’ll discuss this in the next module, where we focus on the Milgram experiment.)

A virtue ethical theory provides an account of the character traits we ought to develop, sustain, and enact. Aristotelianism does this by focusing on the idea of human flourishing, which is often labeled using the Greek term that Aristotle deployed: eudaimonia. The right character traits are those that make for a flourishing human life, a life that is desirable for its own sake and can be called “happy” in a deep, abiding sense.

Aristotle provides a list of traits that he thinks fit the bill for human beings. But rather than go through the details of Aristotle’s list (which was geared toward property-owning men with lots of leisure time in Athens), it would be most useful for you to begin thinking through a list for yourself. Take some time and think about what a flourishing adult life would look like for you. What sorts of activities, relationships, communities, and career pursuits might it involve? Then, think about the character traits (using the above definition of “character trait) that you would need to fully sustain, experience, and enjoy such a life. What kind of person will you need to be?

3.

Once a virtue ethical theory develops its account of desirable character traits, it will then derive an account of ethical reasoning that, rather than appeal to abstract principles, sketches a picture of how someone with the right character traits would respond. What would they notice and feel? What would they prioritize? And how would they then decide and act?

Here, it is important to stress the role that practical wisdom (what Aristotle called phronesis) plays in guiding good ethical reasoning, according to virtue ethics. Most of the morally challenging situations we face are complex, requiring us to weigh many factors, which involve many different persons and relationships. Maturing into an adult life with the right character traits helps us to achieve a measure of practical wisdom that enables us to discern what is important and how to weigh different moral factors.

This feature of the virtue ethical approach highlights a potential weakness in the utilitarian, Kantian, and care ethics views (although less so with the care ethics view, since it resembles the virtue ethical view in some ways). The use of strict, precise principles may not adequately recognize and sift through the complex array of moral considerations that we face in common, challenging situations. For instance, suppose that (returning to the Wells Fargo case) Kathleen Fitzgerald was the sole caregiver for her ailing parent. How is she to balance the need to maintain her work income so as to keep providing for her parent against the importance of not treating customers deceptively? Proponents of virtue ethics observe that there seems to be no general principle that can settle such a conflict. We need mature, virtuous individuals who use their practical wisdom in deciding how to address such situations.

What virtue ethics recommends to you, then, as future employees and leaders in organizations, is not a principle or set of principles to always use in your reasoning. Rather, it recommends that you identify the set of character traits that you ought to develop and that you continue cultivating these traits and preparing to enact them in challenging organizational situations. (We’ll get more specific about what this looks like when we discuss the Milgram study.) There are many paths toward the development of virtuous traits; two that you can take right away are “habituation” and identifying “exemplars.”

Habituation is the regular practice of virtuous patterns of thought and behavior. You think and act as if you fully possessed the virtues, focusing on those virtues that are currently relative deficiencies in your character. Over time, these patterns become a regular part of how you’re prone to think and act. They become habituated as a part of your character.

Identifying exemplars involves identifying individuals of high moral character—people who are worth morally admiring. You closely observe how they carry themselves, how they interact, how they speak, how they organize their activities and relationships. Over time, through observation and imitation, you form a basis for developing the same traits in yourself.

4.

Let’s close this chapter by reflecting on a different kind of workplace moral challenge. It reveals a potential weakness in both the virtue ethics approach and Kantianism, which is interesting, since these two approaches are quite different.

Think about the challenge of dismantling entrenched, socially persistent forms of injustice that show up in workplace structures and patterns of behavior. For instance, groups that are treated as inferior in society at large (on the basis of sexual orientation, race, gender, ethnicity, or religious affiliation) often face barriers to being hired, promoted, and more broadly accepted in workplaces.

Companies have long recognized this challenge and, at their best, have sincerely striven to make progress in overcoming it. A prominent example of a company expressing a commitment to doing this is found in General Motors’ amicus curiae brief to the U.S. Supreme Court in the landmark affirmative action case, Grutter v. Bollinger. This was a case that concerned the race-based affirmative action admissions policies at the University of Michigan Law School. In favor of upholding such policies, GM argued that they aimed to recruit employees who could participate in and support workplaces that incorporated a diverse range of individuals and perspectives. Such employees need to be familiar with the different lived experiences associated with racial, ethnic, and sex-based differences.

Take some time to skim through the GM brief [New Tab].

What’s the problem for Kantianism and virtue ethics here? Well, it is natural to think that, so long as we treat people honestly, fairly, and respectfully, leaving room for them to make their own choices, then we’ve fully applied the Kantian principles. There’s no more that the Kantian principles ask of us. And this seems to fall far short of doing our part to support workplaces that incorporate a diverse range of individuals and perspectives. In particular, it doesn’t seem to require us to actively familiarize ourselves with and appreciate the different lived experiences of those who fall into different social groups and identities from our own.

Aristotelian virtue ethics seems to suggest that, so long as we sustain character traits sufficient for our own flourishing, we’ve done all we need to do. If this leaves some of those in our communities in disadvantaged, marginalized positions, so be it, as long as we are not the ones directly engaged in vicious, marginalizing acts. Note, again, that Aristotle’s own view of virtue was geared toward a subset of Athenians—property-owning men—who enjoyed leisure on the backs of women and slaves who labored for them.

Now, this way of stating the problem is somewhat unfair to the Kantian and Aristotelian approaches. There is surely more to be gleaned from the Kantian principles and the notion of flourishing as eudaimonia that can help address issues of social injustice. But sometimes it helps to have a somewhat exaggerated statement of a moral theoretical problem to think harder and more carefully about the practices of ethical reasoning we want to develop for ourselves. We want to be sure that we aren’t instilling practices that make us satisfied with our own moral credentials while leaving undisturbed the unjust plight of those around us.

References

Aristotle. Nicomachean Ethics. (Original work published ca. 350 B.C. E.) https://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/nicomachaen.html

Hursthouse, R., & Pettigrove, G. (2022). “Virtue Ethics,” in Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ethics-virtue/

Media Attributions

- Aristotle_Altemps_Inv8575

Eudaimonia (εὐδαιμονία): A central concept in Aristotelian ethics, often translated as "flourishing" or "human well-being." It refers to living a life in accordance with virtue and reason, fulfilling one's potential, and achieving a deep, lasting sense of fulfillment rather than mere pleasure.

Literally meaning "friend of the court," an amicus curiae brief is a legal document submitted to a court by someone who is not a party to the case (that is, someone not directly involved in the case) but has a strong interest in its outcome.

Policies and practices that aim to increase opportunities for groups who have historically faced discrimination, such as women and minorities, in areas like education and employment.