Business and the environment

Caroline Burns Ph.D

Learning Objectives

At the end of this module, you will be able to

- Describe principles of environmental sustainability.

- Critically analyze contemporary corporate sustainability practices.

Issues to keep in mind about business and the environment…

Three Approaches to Sustainable Systems

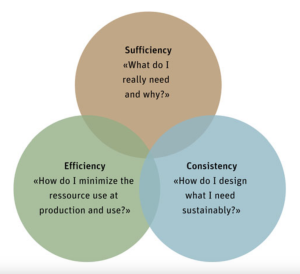

Sustainability in business can be approached in three ways: efficiency, consistency, and sufficiency.

Figure 5.7. The three approaches to sustainability. From Sustainable Business: Managing the Challenges of the 21st Century under a CC-BY 4.0 license. [Image Description]

Efficiency

Efficiency is probably the best-known and, therefore, most intuitive of the three approaches, and it can often be seen, for example, with electrical equipment. It measures the effort and degree to which a source material is transformed into its target state. Low efficiency indicates that large quantities of raw materials and/or effort must be invested to create the desired quantity of the final product, i.e., lots of input and little output. Therefore, low-efficiency systems tend to lead to higher production costs, as resources and effort are usually the main drivers of cost. Therefore, improving system efficiency is a favored approach for most corporations and other organizations, and they have been applying it for decades. The efficiency approach to sustainability means we have a convergence of economic and environmental interests.

An increase in efficiency is, however, often followed by a phenomenon called the “rebound effect.” It describes a common side-effect of reduced production costs: The product price is reduced in order to gain an advantage over the competition. This, in turn, leads to a higher demand for the product, as broader sections of the population can now afford to purchase it, or rather, the same consumers can now consume more of it for the same price. Ultimately, the increased demand leads to increased production, which in turn increases the amount of resources needed and, consequently, has a negative impact on system sustainability. In a nutshell, system sustainability can never only be appraised using relative measures but always has to take total resource volumes into consideration. E.g., the achievement of emitting 10% less greenhouse gases per car produced becomes worthless if 30% more cars are sold and driven on the streets.

Consistency

Consistency strategies do not aim to improve the amount of resources and/or effort as efficiency approaches do, but rather aim to either use infinite, renewable resources or not to allow resources to be transformed into a state where they cannot be transformed into anything useful anymore.

When taking advantage of the few practically unlimited resources—e.g., wind, sunlight, and waves—increasing resource usage does not negatively impact resource availability. There is no less wind on this planet because there are more wind farms. However, transforming those resources into energy requires tools to perform the transformation (wind farms, solar panels, etc.). To be 100% consistent, these tools would have to be sourced from 100% renewable resources, which is mostly not the case. As a consequence, consistency is, in practice, often an approximation towards its goal, trying to optimize the availability and efficient usage of renewable resources.

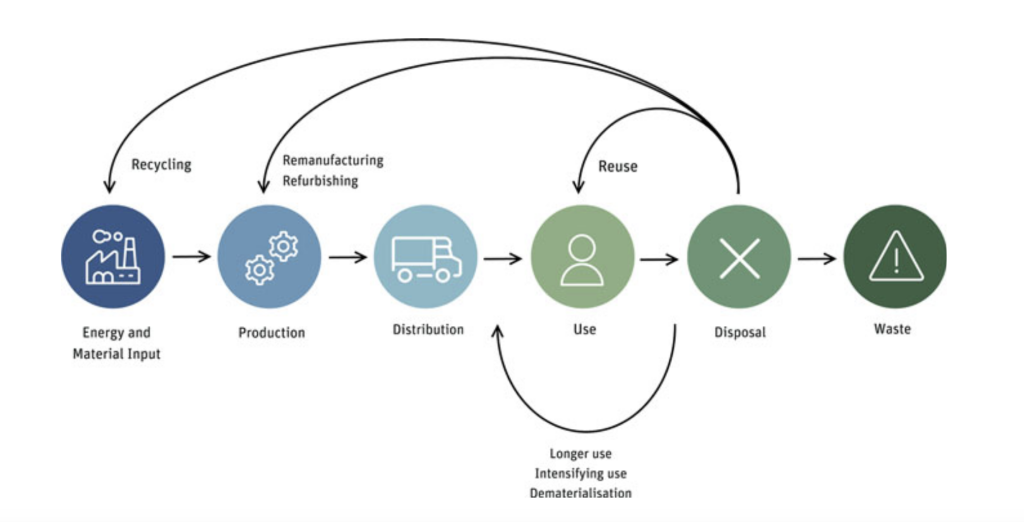

When addressing finite resources, the consistency approach strives to keep those resources as long as possible either in use or at least transformable for their next use. It therefore aims to create resource loops, with the goal to keep these loops as short as possible (see Figure 5.8). The shorter the loop, the less effort and transformation is necessary, and the smaller the effort to keep circularity going. E.g., investing in tool maintenance and therewith prolonging the time the tool is used by the same entity is better than having to transport it to somebody else for continued usage. Having to refurbish the tool to adapt it to a new task takes even more resources, but taking the tool apart and salvaging its materials in order to produce a different tool with them is the last step in a circular setup, as it entails the largest effort and lost energy and material. If the concept of consistency is applied to the economy, the literature speaks of a circular economy.

Figure 5.8. Outline of a circular economy. From Sustainable Business: Managing the Challenges of the 21st Century under a CC-BY 4.0 license. [Image Description]

Sufficiency

While efficiency and consistency approaches address the production side, sufficiency addresses consumption, the basic idea being that reduced demand for a resource leads to less extraction of that resource. There are three primary variants of sufficiency:

(a) Reduction is the simplest and most obvious form of sufficiency. The goal of this approach is a quantitative reduction of the resources used by reducing demand. If people fly less, there will be a reduction in flights and, consequently, a reduction in resource usage and emissions. These effects are mostly directly proportional, so if people travel 30% less, there will be roughly 30% less flights and thus 30% less resources used. As simple as this concept is, it is often the hardest to implement, as it is uncompromisingly effective and, at its core, contradicts the dogma of the last few decades: eternal growth and increasing consumption.

(b) Adaption is closely related to the efficiency approach discussed above, the main idea being that resources are only supplied where there is actual demand, and one can be sure that the resources will be put to use. Applied to the aviation example above, adaption could mean a minimal utilization rate below which the plane would not take off, or a smaller plane would be used since there is not enough demand for this flight. It could also mean a reduction of resource-intensive in-flight features (entertainment, food, air quality, noise reduction, etc.), if there is not a large enough demand for them. The implementation of adaption approaches has been made easier with the introduction of pay-per-use concepts, popularizing the idea of customized offers with equally optimized prices. If, for example, customers had the choice of not buying a laptop at all or buying a feature-heavy model containing 8 CPUs, a GPU laid out for heavy-duty rendering tasks and 512GB graphical memory, a huge SSD hard disk, etc., most of them would buy the laptop offering them all those things they do not need because it is the only option to get the few features, they indeed need. In contrast, an adaptable offer means a more customized product, fewer unwanted features, needing less energy, having wasted fewer resources for building, and including a feature that has never been needed and will therefore not create any added value for the customer

(c) Substitution strives for a reduction, but only in a specific aspect. Instead of staying at home, as the reduction approach would dictate, the plane is substituted by another means of transport, e.g., a train, noticeably lowering the total resource usage and emissions. The impact of substitution measures heavily depends on what aspect is being addressed and what it is being replaced with. Replacing a flight by traveling the same distance alone in a sports car qualifies as substitution but is a relatively weak solution compared to a direct train journey. Consequently, substitution approaches have to be checked thoroughly to assess their consequences.

Adoption Challenges for Businesses

Firms can approach sustainability in three key areas of their business. First, they can improve the environmental impact of what they offer—designing products and services with cradle-to-cradle lifecycle considerations. Second, they can transform how they deliver their offerings through closed-loop production systems that minimize waste and emissions in manufacturing or resource-efficient service delivery methods through digital solutions and optimization of physical infrastructure. Third, they can integrate sustainable business principles into where they deliver goods and services by powering offices with renewable energy, creating hybrid jobs, reducing executive travel, etc. By addressing sustainability through these three interconnected areas—what they make/provide, how they make/offer it, and where they operate—firms can accelerate their transition to business models that don’t negatively impact natural systems.

Sustainability Approaches Within Business Functions

| Functional Areas | Efficiency | Consistency | Sufficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Product and Service Design | Design energy-efficient products

Design with a mind to minimal raw materials.

Mitigate rebound risk

(e.g., energy-efficient appliances or reduced use of rare earth minerals in phone production) |

Use renewable materials or materials in their second life.

Use eco-friendly processes in production and service delivery.

Incorporate cradle-to-cradle principles.

(e.g., using solar power in factories producing wind turbines) |

Market minimalist designs and incentivize customers to purchase only those product attributes needed.

Sell modular products where features can be added to base products.

(e.g., not providing a charger automatically with each new smartphone) |

| Production and Service Delivery Processes | Use closed-loop systems and technology to optimize energy and raw materials use

(e.g., Nike’s water reduction use in textiles) |

Use renewable and recyclable inputs.

By-products for manufacturing should be used as input for another product. |

Avoid overproduction using just-in-time principles.

Calculate demand accurately to avoid waste.

(e.g., Fair Phones) |

| Operations and Infrastructure | Energy-efficient building (Leed Certified)

Reduced water consumption Efficient cooling and heating systems

|

Buy renewable energy

Use eco-friendly products in the day-to-day running of the organization |

Allow hybrid work

Reduce travel (e.g., Twitter’s WFH policy) |

Challenges Facing Business

The approaches to sustainable business above seem reasonable, but they are countered by practical tensions facing business leaders:

- Business favors economic growth models, and inherent in this approach is a challenge to environmental sustainability. More growth equals more resource use and increased negative ecological impact.

- Many pro-environment business activities require capital investment. When cheaper alternatives are available, such capital spending is likely to concern investors.

- Costs can increase when businesses adopt a pro-environment approach to the provision of goods and services, and consequently, this can negatively impact the profit position of a firm. To avoid this, a firm can pass the additional cost to customers. This change in price can result in a negative impact on revenue, as an increase in price is likely to reduce demand.

- The attitude-behavior gap in pro-environmental consumption worries businesses. Firms know consumers want “green” or “greener” goods and services, but those same customers are not always willing to pay for them. So, a firm has to decide what level of risk regarding market share it is willing or able to bear in going green if its pricing strategy is to pass related increased costs to consumers.

- While this is less the case these days, firms don’t always have the in-house expertise or capacity to go green, leading to them needing to incur additional costs in the form of consulting and oversight costs.

- Businesses need substantial time to adapt to environmental programs because change is needed in decision-making, sourcing, operational processes, and reporting. Also, the complexity of implementation increases with organizational size.

References

Fischer, M., Foord, D., Frecè, J., Hillebrand, K., Kissling-Näf, I., Meili, R., Peskova, M., Risi, D., Schmidpeter, R., & Stucki, T. (2023). Sustainable Business: Managing the Challenges of the 21st Century (1st ed.). Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-25397-3

Attributions

“Business and the Environment” by Caroline Burns, Ph.D. is adapted from Sustainable Business: Managing the Challenges of the 21st Century by Manuel Fischer, Daniel Foord , Jan Frecè, Kirsten Hillebrand, Ingrid Kissling-Näf, Rahel Meili, Marie Peskova, David Risi, René Schmidpeter, and Tobias Stucki under a CC-BY 4.0 license. “Business and the Environment” is licensed under a CC-BY 4.0 license.

Image Descriptions

Figure 5.7. This Venn diagram illustrates three complementary approaches to sustainability. Each approach is represented by a colored circle that overlaps with the others. The brown circle at the top is labeled Sufficiency with the guiding question: “What do I really need and why?” The green circle on the lower left is labeled Efficiency, asking: “How do I minimize the resource use at production and use?” The blue circle on the lower right is labeled Consistency, with the question: “How do I design what I need sustainably?” The overlapping layout suggests that these three principles: rethinking needs, reducing resource use, and sustainable design, which interconnect to support sustainable business practices. [Return to Figure 5.7]

Figure 5.8. This diagram visually outlines the circular economy model, showing how materials and products can circulate through a sustainable system rather than ending in waste. It begins with a dark blue circle labeled Energy and Material Input, represented by a factory icon. An arrow points to the next step, Production, shown with two gear icons. From there, materials move to Distribution, represented by a delivery truck icon, and then to Use, shown with a person icon. After use, materials can either go to Disposal (marked with an “X”) and then to Waste (depicted by a triangle with an exclamation mark), or follow alternative, circular pathways. Three curved arrows illustrate how waste can be reduced through circular actions: 1. From Disposal back to Use, labeled Reuse. 2. From Use back to Production, labeled Remanufacturing/Refurbishing. 3. From Disposal and Use back to Energy and Material Input, labeled Recycling. Additionally, a note under the Use stage reads: “Longer use, Intensifying use, Dematerialisation,” encouraging more efficient product usage. The layout shows how circular practices help retain materials in the system and reduce environmental impact by closing the loop. [Return to Figure 5.8]

Media Attributions

- sufficiencyefficiencyconsistency

- circulareconomy