Business Role in Environmental Justice

Caroline Burns Ph.D

Learning Objectives

At the end of this module, you will be able to

- Articulate the disparate impact of environmental issues on groups (geographic, marginalized).

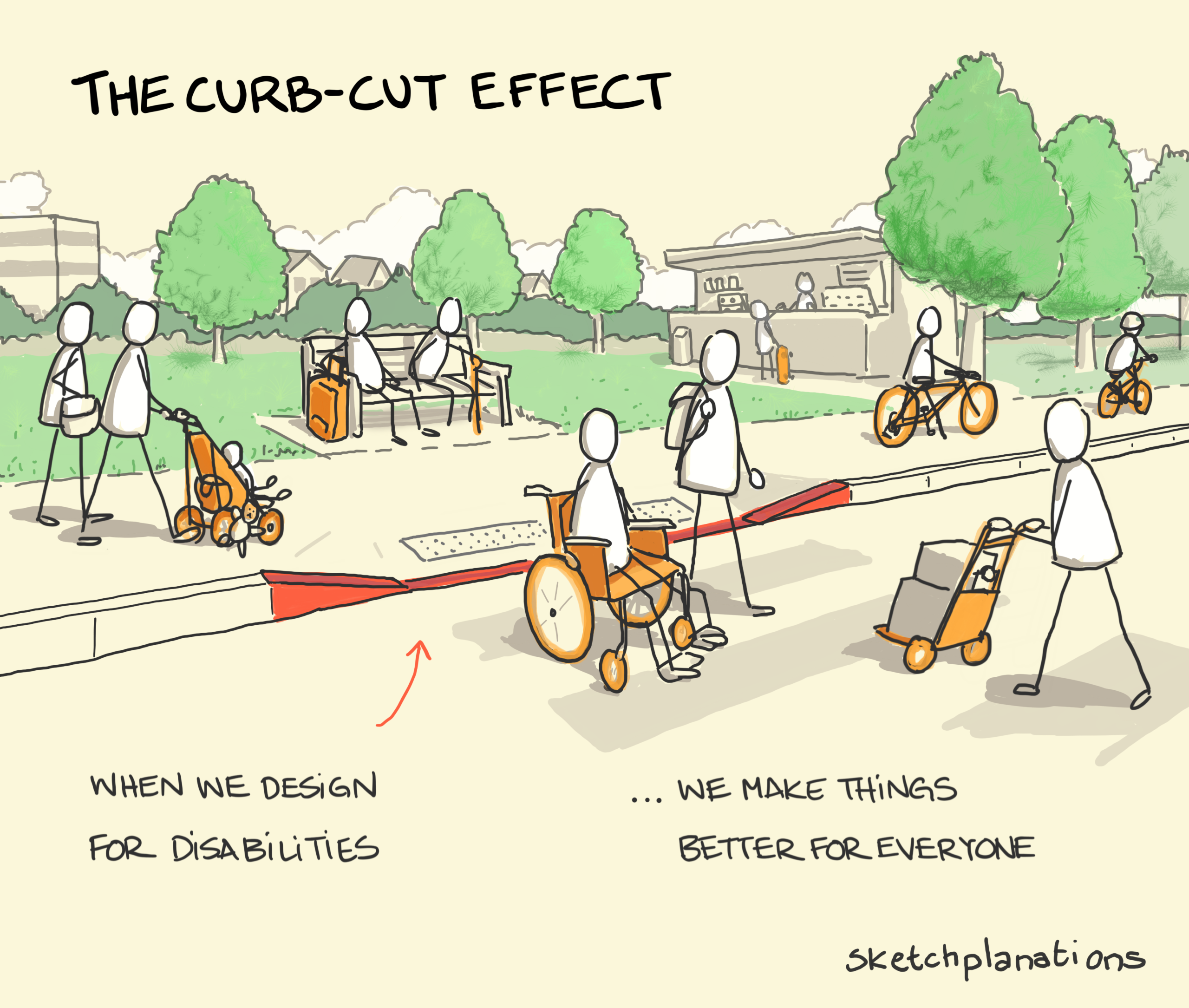

The “Curb-Cut Effect” demonstrates that improving conditions for marginalized groups can uplift all of society. The term “curb-cut” comes from the sloped edges of sidewalks, introduced in the 1970s through the disability rights movement to improve wheelchair accessibility. This change not only helped the disabled community but also benefited parents with strollers, workers with carts, travelers with luggage, and others, enhancing safety and mobility for everyone (Blackwell, 2016).

Figure 4.3. The curb cut effect is the idea that accessibility features designed for one group of people can benefit a larger population. [Image Description]

What we can learn from this is that not only is it in the best interest of vulnerable and marginalized groups that their circumstances improve, but it is in everyone’s best interest. Unfortunately, there is a common belief that supporting one group may harm others. However, evidence shows that helping those most in need can enable marginalized individuals to fully contribute to society and the economy, benefiting everyone. Ignoring the many challenges faced by vulnerable and/or marginalized groups can negatively impact human flourishing, along with the economy. It is incumbent on business to ensure that not only is it doing no harm, but that it is preventing harm and doing good for society. In this chapter, you will be introduced to issues caused and/or exacerbated by business that need to be addressed—for everyone’s benefit—but especially those for whom business activities have been and continue to be especially harmful.

A Story of Environmental Injustice

Environmental Justice Defined

Environmental justice is defined as a “field of study and a social movement that seeks to address the unequal distribution of environmental benefits and harms and asks whether procedures and impacts of environmental decision making are fair to the people they affect.”[1] These social movements have developed in response to environmental racism and other discriminatory practices by which poor and marginalized communities have to live with the impacts of polluting industries while the benefits flow to others outside of the community. In addition, many potential solutions to environmental problems benefit upper and middle-class persons without addressing these disparities.

Social and racial inequalities often manifest themselves in exposure to pollutants. Those who live next to coal mines, oil wells and refineries, and chemical factories bear the brunt of the environmental pollution caused by these industries. Unsurprisingly, these polluting industries are often located next to neighborhoods that lack the political and economic resources to oppose them, almost always poor and disproportionately populated by people of color. This usually happens because these communities lack the political and economic resources to fight against these industries. This is called environmental racism. In rural areas, these polluting industries can provide much-needed employment but also damage people’s health as they are exposed to toxic chemicals. Those who own the mines, refineries, or factories often live in cleaner, safer communities, far from these polluting industries.

Cancer Alley, a section of the Mississippi River in-between Baton Rouge and New Orleans in Louisiana, is an example of this. Louisiana is home to 320 factories that release enough toxic air pollution to have to report to the Environmental Protection Agency. ProPublica reported that St Gabriel’s, a small town of 7,300 located in the middle of Cancer Alley, is 2/3 black with a per-capita income of $15,000, and 29% of its residents live below the poverty line.[2] As a state, Louisiana has some of the most lax air pollution standards in the US. Its standard for benzene, which can cause leukemia, is 60 times higher than Massachusetts. Many of the small towns are unincorporated and don’t have the political power to stop new plants from being built.

Some of the worst environmental racism can be seen in Native American Reservations. Because these reservations are sovereign entities, they are not subject to the same environmental regulations as the rest of the United States. Thus, they have been used as sites for uranium mining, nuclear testing, and the storage of nuclear waste material across the western United States. Native American communities get millions of dollars for their willingness to host these sites, but are also exposed to higher levels of toxic radiation, especially because they are more likely to live off of hunting and gathering food from the areas around these sites.[3]

As highways were built across the United States, they were often built in black neighborhoods, dividing and destroying neighborhoods in order to support the growth of car usage. This automobile infrastructure also encouraged white flight—middle-class white families moving out of the cities into the newly built suburbs. Another problem was redlining. Redlining was the process from the 1930s to the 1960s in which governments drew boundaries around non-white neighborhoods to warn banks, real estate companies, and government agencies from investing in those areas. This restricted the movement of non-white people into certain neighborhoods and worked to racially segregate American neighborhoods at the same time as the civil rights movement and other laws were beginning to make many more overt forms of American apartheid illegal. The United States, despite being a racially and culturally diverse country, is still segregated at the community level as people tend to live close to people who are racially, socioeconomically, and culturally similar to themselves. This segregation is part of what allows environmental racism to continue.

A 2022 study found that 50 years after redlining was declared illegal, its legacy has left 45 million Americans breathing more polluted air. This is because they are often located near highways and major transportation corridors, as well as polluting industries. In addition to air pollution, redlined communities have fewer green spaces, fewer trees on the streets, and other mitigating amenities.[4] This is an example of how systemic racism hurts black families economically and also makes them sicker and more vulnerable.

Something that has reinforced the effects of industrial pollution redlining, in which the worst industries crowd into the poorest neighborhoods, is the NIMBY (not in my back yard) effect, in which more affluent communities are able to pressure corporate and government officials not to build roads, landfills, and other industrial facilities next to their neighborhoods. To some extent, we need to have these industries as we all generate waste and use plastic products, but no one wants to live next to the industries that produce these products that we all use. The fairest solution is to figure out ways to reduce our dependence on these products and find better ways of getting rid of our waste rather than sacrificing some communities for the benefits of others.

Global Environmental Justice

These same processes we see at work within the US are also at work on a global scale. Many of the worst polluting activities have shifted from wealthier countries to poorer countries with fewer (or unenforced) environmental regulations and poorer, marginalized communities that have even less political and economic power than the most marginalized communities in the US. For example, the most pollution-heavy mining and industrial activities now happen in relatively poor countries South America, Africa, and Asia. The result is that while air and water pollution have been improving in the developed world for decades, they have been getting worse in developing countries. These global supply chains are increasingly complex, which makes it difficult to quantify the impact caused by the production of our smartphones, shoes, or latest toys.

Social scientific theories like Wallerstein’s world systems theory and development theory can help us make sense of these global supply chains. World Systems theory divides the world into the core, the semi-periphery, and the periphery. The economy of the core is dependent on information, and its main industries are banking, cultural production (the internet, entertainment, and advertising), education, and other knowledge industries. The semi-periphery involves industrial manufacturing, while the periphery is involved in mining raw materials and other extractive industries. Rather than being separated, each one is maintained in place by its relationship with the others. Poor underdeveloped countries are not underdeveloped because they are somehow further back along the development highway. They are underdeveloped because they are exploited and marginalized by global systems of power.

Africa, one of the poorest regions of the world, has an abundance of oil, gold, diamonds, minerals, and other valuable natural resources. These resources are extracted and exported, making millions of dollars for a tiny African elite and extractive industries based in Europe and North America. The pollution from these industries impacts local health and livelihoods, while the benefits are largely exported. Many of our consumer electronics and old clothing, once broken, are shipped to Africa. The electronics are dismantled and recycled, often resulting in unsafe working conditions and health impacts. The used clothing from the developed world is often sold in Africa at very low prices, destroying local clothing manufacturers who cannot compete with the cheap bales of used clothing coming in from abroad. Although most of us have not traveled to Africa, our economic consumption and waste impact their lives through global supply chains. In 2020, three of Hawaii’s top ten importers were Libya, Angola, and Congo, all of which supplied oil, which is our largest import at over a billion dollars a year.[5] The next largest import is cars, which we need to use the oil.

Climate Change and Environmental Justice

In addition to the impacts of toxic pollution, climate change disasters like flooding, sea level rise, droughts, and hurricanes will impact many areas in the global south worse than areas in the global north. Some of this is due to geographic factors, but it is also due to political, economic, and social factors. For example, low-lying island nations in the Pacific like Kiribati or the Maldives in the Indian Ocean will lose much of their territory or even disappear as the sea level rises. Farmers in Africa, dependent on rainfall, will become increasingly impacted by droughts. Within these countries, the poorest and most marginalized communities will be the most vulnerable because they don’t have the resources to move to avoid these impacts or to mitigate them by reinforcing their homes, building up shorelines, or buying food shipped in from other parts of the world.

The cruel irony in these differential impacts of climate change is that the communities that will be hardest hit by climate change are those who have contributed the least to its causes. In some cases, they do not have electricity, do not own cars, and have never flown on a plane. They do not participate in the consumption of industrial goods or the global food supply chains that have caused the climate crisis. Many of the poorest in the world still operate within local supply chains, growing and raising their own food and purchasing few manufactured goods.

Alternatively, those who live in the global North, which includes Europe and North America, participate in the economies and governments that have been the primary drivers of climate change since the Industrial Revolution. We also have the resources to move houses back from the ocean, dig wells to access more water, electrify our houses, and purchase electric cars. Of course, within these societies, these resources are not evenly distributed, as when Hurricane Katrina slammed into the Gulf Coast as a Category 5 hurricane in 2005, displacing over 1 million people and causing 100 billion in damages that disproportionately impacted communities of color. [6]

From this perspective, there are no truly natural disasters. While hurricanes, floods, or wildfires are natural, the distribution of their impacts is always affected by economic, social, and cultural factors. Government aid also moves unevenly, helping some communities quicker and more effectively than others. In September of 2017, Hurricane Maria made landfall in Puerto Rico as a Category 5 hurricane. There was an estimated 90 billion dollars in damages, with 95% of residents without power or cell phone services. Even though Puerto Rico is a US territory and its residents are US citizens, the federal response was slow, and in January 2019, almost a year and a half later, 350,000 people still lacked electricity. Even now, four years later, there is a significant amount of infrastructure work that has not been completed. This lackluster response is due, in part, to ongoing histories of colonialism and racism.[7] Environmental activists are suggesting that the island adopt more renewable energy, smaller energy grids, and other measures that simultaneously build resilience and provide more equitable access to electricity.

One response to the destruction wrought by climate change will be migration, as people in areas hit hard by droughts, fires, and floods seek to move to other areas less impacted. The massive Syrian refugee crisis across Europe, resulting from the Syrian civil war, was also caused by an ongoing drought in the region that exacerbated tensions and created the conditions for civil unrest. The developed world can respond with compassion and accept refugees or turn them away, allowing huge refugee populations to live in political, socioeconomic, and cultural limbo in refugee camps built along geopolitical borders. Our immigration policies are part of our climate change response. Do these policies reflect a scarcity mentality in which we need to fight to keep what is ours and exclude others, or do they reflect a willingness to open our borders and allow others who are trying to improve their lives to participate in the American dream? These are not theoretical questions as different political parties fight over immigration policies that can have a dramatic impact on migrants’ lives. With climate change, the scale of migration will dramatically change.

There are within the US and Europe the development of nationalist and eco-fascist movements that recognize the societal threat of climate change but offer nationalism and the closing of borders to “undeserving” outsiders as a solution.[8] These movements often focus on overpopulation as the cause of environmental destruction and see reducing the number of certain kinds of humans as beneficial. These anti-immigrant sentiments fail to realize that many of the problems in the developing world, even those that seem natural, are often the result of political and economic policies that left these countries vulnerable and underdeveloped in the first place.

Video 4.1. The Fight for Environmental Justice in Michigan by MLive

Video 4.2. The Father of Environmental Justice Reflects on the Movement He Helped to Start by Scientific American

References

Blackwell, A. G. (2017). The curb-cut effect. Stanford Social Innovation Review, 15(1), 28-33. https://ssir.org/articles/entry/the_curb_cut_effect

Attributions

“Business Role in Environmental Justice” by Caroline Burns, Ph.D. is adapted from “Environmental Justice” by Christian Palmer, PhD, under a CC-BY 4.0 license. “Business Role in Environmental Justice” is licensed under a CC-BY 4.0 license.

Image Descriptions

Figure 4.3. This cartoon-style illustration depicts a sidewalk scene centered around a curb cut, which is a ramp built into the curb to allow smooth access between the street and sidewalk. A person using a wheelchair is moving up the curb cut, while nearby, others also benefit: a person pushing a stroller, someone pulling a wheeled suitcase, a delivery worker with a hand truck, a child riding a scooter, and a bicyclist, all using or approaching the curb cut. The background includes trees, park benches, and a bus stop. The text at the top reads: “The Curb-Cut Effect.” Below the ramp, two phrases appear: “When we design for disabilities…” and “…we make things better for everyone.” The artwork conveys the principle that accessible design benefits a wide range of people, not just those with disabilities. [Return to Figure 4.3]

- Bryant, B. and J. Callewaert (2003) Why is understanding urban ecosystems important to people concerned about environmental justice? pp. 46-57. In A.R. Berkowitz, C.H. Nilon and K.S. Hollweg (eds.) Understanding urban ecosystems: A new frontier for science and education. Springer-Verlag, New York, NY. ↵

- Baurick, T. (2019) Welcome to "Cancer Alley," where toxic air is about to get worse. www.propublica.org ↵

- Cultural Survival Quarterly (1993) Nuclear War: Uranium mining and nuclear tests on indigenous lands. www.culturalsurvival.org ↵

- Fears, D. (2022) Redlining means 45 million Americans are breathing dirtier air. 50 years after it ended. The Washington Post. March 9th, 2022 ↵

- Stacker (2021) Countries Hawaii imports the most goods from. stacker.com ↵

- Editors. (2019) Hurricane Katrina. www.history.com ↵

- Gibson, C. (2017) How colonialism and racism explain the inpet US response to Hurricane Maria. www.vox.com ↵

- Shukla, N. (2021) What is Ecofascism and why it has no place in environmental progress. www.earth.org. ↵

The network of organizations, people, and activities involved in creating and delivering a product from raw materials to the final consumer.